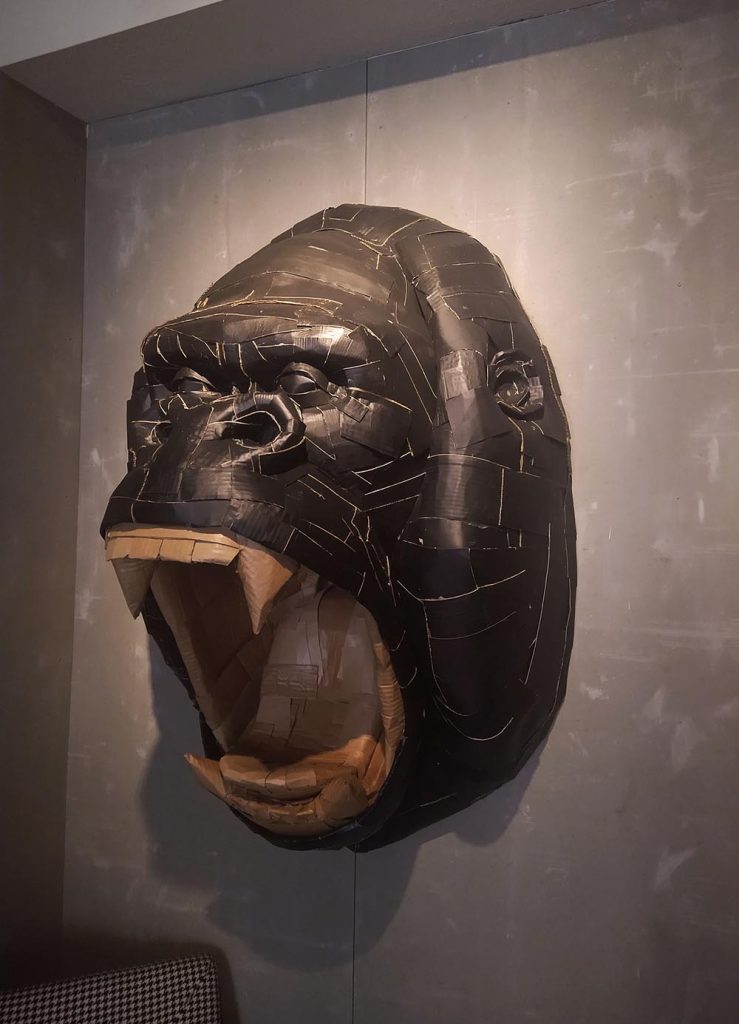

Makoto Aida has the ability to simplify a complex concept into a roaring vision of chaotic poetry and grotesque beauty. His art explores the dynamics of the Japanese psyche, incorporating young girls, businessmen, war and politics. Some of his paintings are so big and painstakingly detailed that they take years to complete. For the next several months, the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo, Japan is holding a retrospective exhibition that spans his 20-year career. Aida’s art includes manga-style painting, traditional Japanese painting, photography, sculpture, video and installation. When Hi-Fructose caught up with the artist, he was at the museum working on an on-going project called, “The Monument of Nothing.” It’s a series of sculptures constructed only out of cardboard and tape. To assist him, he enlists young artists of any skill level to volunteer their time and effort to create their own sculpture. During the interview Aida talked about various topics ranging from his upbringing in a strict household, to merging storytelling into his art.

Since your father was a sociology professor, what influence did this have on your art? How did he influence you to become an artist?

I decided to become an artist when I was 16 years old. Whether my father had a real influence on me upon deciding to become one… I don’t know, I guess you can say, yes and no [laughs]. As far as I can remember, I was always a rebel to my father since he and my mother were both teachers and naturally, a pair of what we can call “conformists.” Perhaps because they were parents, they always somehow looked conservative to my eyes, too, and my father was a man farthest away from being “edgy” or “radical.” As a matter of fact, I’ve thought about any possible influence by my father… regardless of whether on conscious or subconscious level. Either way, one thing I’ve found it personally curious, even to this day, is that I have ended up doing more or less the same as what my father — whom I’ve always perceived as someone different from myself and whom I was rebelling against — did professionally. He analyzes the society and makes commentaries on the society — and at first glance, we might appear to be engaged in completely almost opposite things, but the truth of the matter is that I’m doing the same, but just through different means (my artworks) or different channels, I guess.

Your work brilliantly reflects taboos in modern Japanese society. Do you think the themes in your work are lost in translation when considering the international community?

Even if the audience is of Japanese national, some of my works needs explanation. Some of it doesn’t. I am sure they tend to understand them better or more easily than, say, foreigners. To be honest, though, I am not too concerned if the themes or messages in my artworks get lost in translation. At times, I do not even feel that all the people who face any of my artworks must understand what is behind those artworks. I do have a very strong desire for people to look at my artworks, though.

How do you challenge yourself at this point in your career?

The fact that my largest influence while growing up was Yukio Mishima may have something to do with this, but I would like to start thinking about putting some stories or narratives forward at some point. All my life I’ve concentrated on making artworks whose interpretations are up to the viewers more or less, but what each artwork represents is rather fragmentary. If you see all of the exhibited works in this exhibition, you would know that there are lot of things in my mind, rather chaotically… I do also acknowledge that there are various styles or modes of expression in my body of work and a lot of people say that that I do not have one, particular “signature style” if you see what I mean. But it is my ambition that someday I do that — produce something that has its own story and have the narrative felt by the viewers. I did enjoy making this work called Mutant Hanako, which, you can say, was a comic book originally [The English-dubbed film version of it is exhibited in the gallery we colloquially call “R-18 Room” in this exhibition]. I know the storyline of Mutant Hanako was extremely absurd and is a total “nonsense” in nature, but yes, I want to do something in that vein. I want to elaborate on narratives or stories, regardless of whether it be novel-writing or film-making.

What do you think Japan will be like in the next 20 years?

Because there’ll be less and less kids and the Japanese economy would be steadily declining, I think Japan will be a very small and poor country, economy-wise. In its process, however, people will hopefully learn to make ends meet at least, and also learn to make their lives, in general, much simpler to adjust to such social state / circumstances then. I think I will be more than happy, as long as there remains a solid, mature culture here.

Kawaii is the dominant culture in Japan. How do you combat this or incorporate it in order to keep your work interesting?

It is a strange thing to say, but I did grow up among what they call “kawaii culture.” I say strange as we all take it for granted. I guess we’ve been exposed to such [kawaii] images without even realizing it. They are everywhere so, it’s always been in my subconscious. I do not take this whole thing too negatively, but still I am a man, I am not fanatically into what is considered kawaii in general. I guess you could say that I do incorporate the idea, or what I consider kawaii into my work unconsciously.

Have things changed in the art world since you first started your career? Is there anything you miss from the early ’90s?

Maybe it is better to say I started my career as a young student of art in the ’80s. When I was a student of art — well, we come from the generation where there was an atmosphere that art is something supposedly “serious.” Those who were involved in art education taught us to take art serious — almost excessively — and I was feeling discomfort about the whole art education system. I never really felt there really was not much freedom, and being in the art university’s oil painting department, I was taught to concentrate on oil painting, instead of experimenting on new wave of expressions such as “installation” — that word was still very new by the way [laughs] — or exploring new media. Nonetheless, the decade was terrible. In Japanese society, the “bubble economy” was at its peak, where regular people would be spending more and more money, manically. Everything about everything then, well, at least in Japan at that time, was all about money, and contemporary art or art in general was no exception. I was never a kind of painter or student of art that even attempted to be on the commercial art circuit, either. Now that I think about it, that’s one thing about me as an artist that never changed and will probably never change.

Anyway, I was skeptical young artist then, the whole thing just felt too shady to me and I was also afraid of being sucked into the large, beastly system. So, anything that had something to do with art dealing, art collectors or art market, I didn’t really like. Things smelled too much of money; and it was so not the money that I became the artist for. So, to be perfectly honest with you, I just don’t miss that time, I think I like it much better now.

Do you see your influence on young up and coming artists?

I do enjoy working with younger artists and looking after them, but you know, the funny thing is, that most of those “young artist-friends” of mine have different styles from mine. What they are thinking are very different from what I used to think when I was at their age, or what I think now. But we do get along. I guess I can offer them what they are missing and vice versa. We feed off of each other as an exchange, so it is a mutually beneficial and stimulating relationship, I think rather than a teacher-student relationship, a master-disciple relationship, or a mentor-protégé type of relationship.

You have a young son. What’s your advice to him if he wishes to become an artist like his father?

I wouldn’t advise against his wishes, as once he says he wants to become an artist then it means that he really does. And there seem to be some signs that he might want to start to insist that he would want to become one… [sigh]. The most constructive advice I could give him then, however, would be to recommend a different genre. I am his father and I guess you could say my name has been made as a contemporary artist of this generation; and it’s fine that he would follow in my footsteps and enter this field, but I would still recommend a different genre, you know? [laughs]